|

Expert

Analysis

One

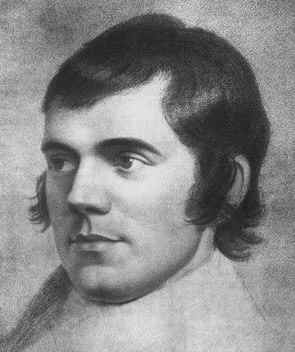

of the greatest problems encountered by many people reading Burns material,

is the language itself. Whilst Burns wrote in English, much of his work

was in the old Scottish dialect…….often difficult even for a

Scot to understand today ! Similarly, as the years have gone by, new material

has been uncovered, thus bringing new challenges.

Dr. Jim. Mackay, (who wrote "The Burns A to Z, The Complete Word Finder")

has written the following article for The World Burns Club, which provides

an interesting history on how, over the years, the problem has been tackled.

Expert

Analysis by Dr. James A Mackay

"Burns

Had a Word for it"

It was in 1889 that Messrs Kerr and Richardson of Glasgow published A

complete Word and Phrase Concordance to the Poems and Songs of Robert

Burns. This large volume of 560 pages had been compiled and edited by

the Revd John Brown Reid, minister of Wigtown Free Church.

It was in 1889 that Messrs Kerr and Richardson of Glasgow published A

complete Word and Phrase Concordance to the Poems and Songs of Robert

Burns. This large volume of 560 pages had been compiled and edited by

the Revd John Brown Reid, minister of Wigtown Free Church.

That a minister should be interested in the works of Burns a century ago

was rather unusual in itself, but for Reid the poems and songs of Scotland's

National Bard became an obsession which occupied all of his leisure time

over a period of many years. Reid, the son of a mining engineer, graduated

M.A. and had a distinguished academic career before entering holy orders.

He served at Morpeth for some time as assistant to the Revd Dr James Anderson,

whose daughter Frances he married in 1879, a year after he was ordained

as the minister of Wigtown Free Church. He laboured in that charge for

twenty-two years and died at Wigtown on 5 September 1900.

Reid conceived the idea of compiling his Concordance of Burns because

Shakespeare had his, and even lesser poets, such as Tennyson and Cowper.

Burns might not be a voluminous writer, he argued, but nevertheless no

fewer than 600 distinct pieces were credited to him. 'The difficulty of

verifying a quotation, finding a phrase, a happy expression, or the exact

words of a passage, is further augmented by the hopeless character of

the Index to any Edition that may be possessed.'

Reid conceived the idea of compiling his Concordance of Burns because

Shakespeare had his, and even lesser poets, such as Tennyson and Cowper.

Burns might not be a voluminous writer, he argued, but nevertheless no

fewer than 600 distinct pieces were credited to him. 'The difficulty of

verifying a quotation, finding a phrase, a happy expression, or the exact

words of a passage, is further augmented by the hopeless character of

the Index to any Edition that may be possessed.'

Unfortunately, Reid's Concordance appeared all too soon. Within a decade

there had appeared two new editions of the works of Burns, the Wallace-Chambers

and Henley-Henderson, which between them raised the standards of Burns

scholarship to a new level.

To be sure, the Burns Federation had been in existence for four years

when Reid's magnum opus was published, but a further two years were to

elapse before the Federation's own annual publication, The Burns Chronicle,

made its debut. One of the earliest tasks of the Chronicle's long-term

editor, Duncan McNaught, was to produce a list of works often claimed

as written by Burns but which were now regarded as spurious.

About thirty of the poems and songs indexed by Reid, in fact, came into

that category. On the other hand, more than a hundred pieces have been added to the canon

since 1889, largely as a result of the labours over more than four decades

by the late Professors Dewar and Kinsley. Many of the bawdy poems of Burns,

which actually feature in the poet's voluminous correspondence, had been

omitted from the standard editions of his works on grounds of good taste,

and it was not until 1968 that they were admitted to the standard editions,

although they had previously appeared in The Merry Muses of Caledonia,

itself a clandestine publication until the 1950s.

the other hand, more than a hundred pieces have been added to the canon

since 1889, largely as a result of the labours over more than four decades

by the late Professors Dewar and Kinsley. Many of the bawdy poems of Burns,

which actually feature in the poet's voluminous correspondence, had been

omitted from the standard editions of his works on grounds of good taste,

and it was not until 1968 that they were admitted to the standard editions,

although they had previously appeared in The Merry Muses of Caledonia,

itself a clandestine publication until the 1950s.

One of the major disadvantages of Reid's Concordance was the use of titles

for poems and songs which were completely arbitrary. Many of Burns's compositions

were untitled, and this explains why different titles appear in different

editions. A high proportion of the titles used by Reid were those fashionable

in the nineteenth century but long since obsolete and little understood

nowadays.

As far back as 1913 Duncan McNaught recognised the need for a more up-to-date

Concordance, but two world wars and countless economic and social upheavals

have since intervened. In the 1960s a straightforward reprint of Reid's

Concordance was produced in the United States and, more recently, a similar

reprint was at one time contemplated in England, but the project was aborted

after great consideration.

In 1985 the Burns Federation celebrated its centenary and commemorated

the occasion by publishing its official history. This focused attention

on the fact that publications to promote the life and works of Burns had

been one of the principal aims of the founding fathers of the Federation

in 1885 but, apart from The Chronicle, little had been done in the intervening

century to implement this aim.

Out of this arose The Complete Works of Robert

Burns, which was published jointly by the Burns Federation

and Alloway Publishing Limited in July 1986 to mark the bicentenary of

the Kilmarnock Edition, and the companion volume of November 1987 devoted

to The Complete Letters of Robert Burns.

It seemed logical, therefore, to publish a new edition of Reid's Concordance.

To this end Gordon Mackley of New South Wales, an Honorary President of

the Burns Federation, very generously put up the sum of £1,000 towards

the costs of publishing this work, which eventually saw the light of day

as Burns A to Z: the Complete Word Finder.

Originally it was thought that it would be sufficient to reprint Reid's

Concordance, together with a supplement of about 50 pages which, it was

hoped, would incorporate the poems and songs which had been ignored by

Reid. A detailed survey of Reid's Concordance, however, very soon revealed

that this solution would be impracticable.

In the first place, the omissions (amounting to about 15 per cent of the

whole) were very much more substantial than anticipated. Secondly, the

use of titles which, in many cases, were not generally recognised, rendered

the utility of the main body of the work very doubtful. Thirdly, the inconvenience

for the reader of having to look up words and phrases in two separate

parts of the volume was soon appreciated.

It was eventually recognised that there was no alternative but to start

completely afresh. This entailed the computerisation of The Complete Works,

with a separate entry for each keyword (nouns, verbs, adjectives and adverbs).

Pronouns, prepositions, conjunctions, articles and particles, as well

as the verb 'to be' and auxiliary verbs were omitted.

This meant that, on average, a line of verse would contain four or five

keywords. The reader seeking the source of a quotation only needs to know

one of these keywords in order to locate the line. Oddly enough, there

are several lines which do not contain any keywords in the above criteria:

Like you or I. (Epistle to John Rankine)

Like you or me. (Epistle to William Simpson)

Had it not been for you! (Epistle to Davie)

It is this - and it's this - and it's this (I'll tell you a Tale of a

Wife)

To her, and to him, (While Prose-works and Rhymes)

Reid's Concordance contained over 11,400 words and almost 52,000 quotations;

the Word Finder encompasses about 15,000 words and almost 80,000 quotations.

The vast difference is only partly explained by the 100-odd poems and

songs which have been admitted to the canon since 1889.

One of the problems encountered in the aftermath of publishing The Complete

Works was the number of poems which many people believe to have been composed,

in whole or part, by Burns, but which have long since been rejected by

most editors and scholars, either on stylistic grounds, or because publication

before Burns's time has subsequently been proved. And this misleading

process still continues; as recently as 1994 an anthology of bird poetry

included 'Ode to the Owl' with an attribution to Burns, hitherto unrecorded

but unsubstantiated.

Controversy continues to rage, for example, over the Selkirk Grace (which

in its vernacular form was known as a Galloway Grace long before 1793

when Burns rendered a version extempore in Standard English); or the long

poem entitled 'Look up and See' which first appeared in James Barke's

edition of 1955 and has since been reprinted many times by Collins, but

which as long ago as the 1920s was unmasked as a fabrication of William

Stewart Ross who first published it pseudonymously in The Agnostic Journal

in 1904.

Controversy continues to rage, for example, over the Selkirk Grace (which

in its vernacular form was known as a Galloway Grace long before 1793

when Burns rendered a version extempore in Standard English); or the long

poem entitled 'Look up and See' which first appeared in James Barke's

edition of 1955 and has since been reprinted many times by Collins, but

which as long ago as the 1920s was unmasked as a fabrication of William

Stewart Ross who first published it pseudonymously in The Agnostic Journal

in 1904.

More recently,

in the bicentenary year of the poet's death, the claims by Patrick Scott

Hogg to have discovered numerous radical poems of Burns, published anonymously

in various newspapers of the 1790s, created a sensation that went far

beyond Burns circles. Greeted with scepticism at the time and the subject

of much heated controversy since 1996, some of these poems were subsequently

found to have been composed by Captain William Johnston, the editor of

the Edinburgh Gazetteer in which they were published.

The bulk of these controversial pieces was later proven by Dr Gerard Carruthers

to have been the work of Bishop Alexander Geddes, a Catholic prelate whose

brother, Bishop John Geddes, was a friend of Burns and the proud possessor

of the so-called Geddes Burns, a copy of the first Edinburgh edition (1787)

in which the poet inserted a number of poems, in manuscript, which he

had written in the course of his Highland tour. The actual manuscripts,

in Geddes's handwriting, were rediscovered lately in England where they

had reposed for 200 years.

The late Professor Kinsley identified some 52 poems which had been claimed,

at one time or another, as being by Burns. More recent research has more

than doubled that number, and this is confined to those which (prior to

Hogg in 1996) had appeared in periodicals or anthologies as the work of

Burns but which had either been in print before Burns's time, or were

attributed to other poets, or rejected on chronological or stylistic grounds.

One of the problems that bedevil Burns scholarship is the number of variations

that exist in the countless published editions. Not only did Burns revise

poems between their first publication in the Kilmarnock Edition of 1786

and the Edinburgh editions of 1787 and 1793, but works which were not

published until after his death were based on manuscripts. Burns frequently

made copies of his poems for his friends, and these copies often incorporated

revisions, second thoughts and improvements.

As successive editions, mainly in the nineteenth century, derived their

texts from different manuscripts, it is understandable that apparent discrepancies

should arise. In addition, there were many instances where Burns cancelled

or suppressed lines, the most notable example being the passage in "Tam

o Shanter' which appeared in Grose's Antiquities of Scotland (1791), but

which he excised from the 1793 Edinburgh Edition on the advice of Dr Blacklock.

When I embarked on this task I had no idea of its immensity or complexity.

In many respects the computerisation of the lines was the easy part of

the project. The problems stretched into infinity when it came to translate

the material in this database into a word-processing mode, in such a manner

that quotations were not only grouped according to their keywords, but

also, within these groupings, in an order convenient to the user. A perusal

of Reid's Concordance shows the quotations in an apparently random order.

In fact, they were arranged according to the alphabetical order of the

titles, but as these were so often arbitrary, or unfamiliar to present-day

readers, the logic of this sequence is not always apparent. Trying to

find the correct quotation under such keywords as 'Love' or 'Fair' thus

becomes akin to searching for the proverbial needle in a haystack. In

the Word Finder, however, the lines are arranged in alphabetical order,

so that if the reader knows the line in question it can readily be found.

In that way it becomes a relatively easy task to find the reference to

'love' that you want - out of the 394 lines of Burns in which that word

appears.

When I embarked on this task I had no idea of its immensity or complexity.

In many respects the computerisation of the lines was the easy part of

the project. The problems stretched into infinity when it came to translate

the material in this database into a word-processing mode, in such a manner

that quotations were not only grouped according to their keywords, but

also, within these groupings, in an order convenient to the user. A perusal

of Reid's Concordance shows the quotations in an apparently random order.

In fact, they were arranged according to the alphabetical order of the

titles, but as these were so often arbitrary, or unfamiliar to present-day

readers, the logic of this sequence is not always apparent. Trying to

find the correct quotation under such keywords as 'Love' or 'Fair' thus

becomes akin to searching for the proverbial needle in a haystack. In

the Word Finder, however, the lines are arranged in alphabetical order,

so that if the reader knows the line in question it can readily be found.

In that way it becomes a relatively easy task to find the reference to

'love' that you want - out of the 394 lines of Burns in which that word

appears.

Some modern concordances do not distinguish between the usages of words

but merely lump all quotations together under a single heading. Reid,

however, was meticulous in differentiating verbal, adjectival or adverbial

usages of words as well as distinctive meanings, and I adhered to this

practice, even though this greatly compounded the work involved. The word

'like', for example, may be a noun, a verb, an adjective, an adverb, a

conjunction or a preposition. The first four were indexed; the last two

were omitted. Vernacular or archaic keywords have their meanings in parentheses.

Times have moved on and much more is known and understood of Robert Burns,

the man, his poems, ballads, songs and letters. On a personal note, I

enjoyed immensely, the significant challenge of preparing the "Complete

Works Trilogy" and now look forward to The World Burns Club , using

modern technologies and fresh ideas, help make the life and works of Robert

Burns even more accessible to a growing worldwide audience.

Article contributed

by Dr James A. Mackay (January 2000) Dr Jim Mackay is one of the

worlds leading authorities on Robert Burns. He is author of the

acclaimed trilogy "The Complete Works of Robert Burns"

"The Complete Letters of Robert Burns" and "Burns

A - Z, the Complete Word Finder.

In addition he wrote the massively successful "Braveheart" -

the factual biography of William Wallace. Thank you Jim for your

valuable input!

|